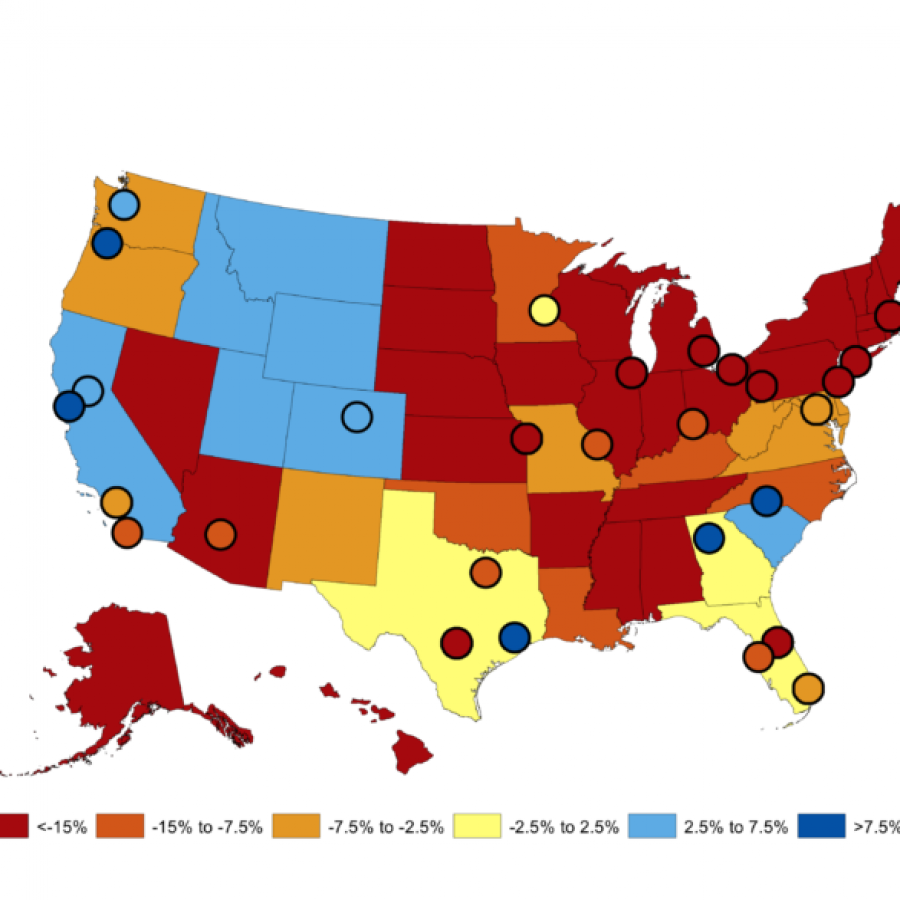

Only a handful of states, colored in blue, are predicted to see an increase in the number of students attending regional four-year colleges and universities between 2012 and 2029. The rest will see declines in students. In the red-colored states, the drop in students will exceed 15%. The dots represent large metropolitan areas. These urban college markets, such as San Diego, may diverge from their state’s or region’s trends. Nathan D. Grawe, Carleton College

What does the declining birthrate mean for colleges and universities and the students who hope to get a college degree a decade from now? The answer depends on where you live in the United States and how selective the college is. For most colleges and universities, the outlook is grim. But that could be a good thing for their future students.

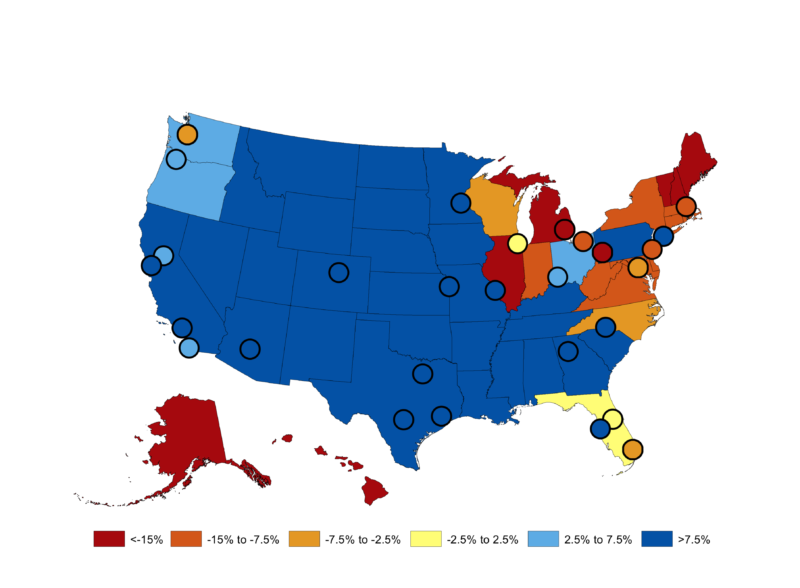

But student demand is expected to grow for the nation’s most elite colleges and universities between 2012 and 2029. The dots represent large metropolitan areas, which sometimes diverge from their state’s growth forecasts. Nathan D. Grawe, Carleton College

Nathan Grawe, an economist at Carleton College in Minnesota, predicts that the college-going population will drop by 15 percent between 2025 and 2029 and continue to decline by another percentage point or two thereafter.

“When the financial crisis hit in 2008, young people viewed that economic uncertainty as a cause for reducing fertility,” said Grawe. “The number of kids born from 2008 to 2011 fell precipitously. Fast forward 18 years to 2026 and we see that there are fewer kids reaching college-going age.”

Birthrates failed to rebound with the economic recovery. The latest 2017 birthrate data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention posts new lows, marking almost a decade of reduced fertility.

Related: Colleges welcome first-year students by getting them thinking about jobs

But not all colleges will feel the pain equally. Demand for elite institutions — the top 50 colleges and 50 universities, as ranked by U.S. News & World Report — is projected to drop by much less during the 2025 to 2029 period (18 years following the birth dearth). And student demand for elite institutions may be 14 percent higher in 2029 than it was in 2012. Meanwhile, regional four-year institutions which serve local students are expected to lose more than 11 percent of their students, from 1.43 million in 2012 to 1.27 million in 2029.

The Northeast, where a disproportionate share of the nation’s colleges and universities are located, is expected to be the hardest hit. By contrast, mountain states where there are fewer students and fewer colleges, such as Utah and Montana, may see slight increases in student demand.

Grawe’s forecasts for the number of students at two-year community colleges and four-year institutions are published in his book, Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education, with updates on his website. He breaks the numbers down not only by type of school, and how selective it is, but also by geographic region and race/ethnicity.

Why do the forecasts sometimes move in opposite directions? Grawe explains that elite colleges are less affected by the birth dearth because they’re a small niche market of fewer than 200,000 students that has benefited from the explosion in college education since the 1980s.

“The people who went to college 20-30 years ago and got a degree, they’re now the parents of kids who are looking at going to college in the next 10 years or so,” said Grawe. “If your parents went to college, your probability of going to college is much higher and your probability of going to a highly selective four-year college is a lot higher.”

Related: Bending to the law of supply and demand, some colleges are dropping their prices

Giving an extra boost to elite demand is the Asian-American population. Because of new arrivals from India and China, they’re the fastest growing race or ethnicity in the country. “They have a high attachment to higher education in general and elite higher education in particular,” said Grawe.

Meanwhile, less selective institutions are not as likely to buck the powerful demographic trend of declining birthrates.

Northeastern schools, especially those who cater to students who live nearby, are feeling more pain because of demographic shifts that began well before the Great Recession hit. Americans are continuing to move away from the Northeast to the South, to places like Texas. In addition, birthrates are lower in the Northeast where there is a smaller Latino population. Latinos have historically had the highest fertility rates among U.S. racial and ethnic groups.

This may be good news for students who are currently in fifth grade and younger. Grawe predicts they’ll have an easier time getting admitted to schools as colleges fight more fiercely for the available students.

“Students are going to be a hot commodity, a scarce resource,” said Grawe. “It’s going to be harder during this period for institutions to aggressively increase tuition. It may be a time period when it’s a little easier on parents and students who are negotiating over the financial aid package.”

For the colleges themselves, declining student enrollments will likely translate into fewer tuition dollars collected and leaner budgets. Regional colleges will be under pressure to cut liberal arts courses and expand professional programs, such as law enforcement, that students feel will translate into a good-paying job. “As a liberal arts professor, it’s heartbreaking,” said Grawe. “But you can understand. The institution’s existence is dependent on meeting the expectations of the student.”

Some colleges won’t make it. Moody’s Investors Service is predicting an uptick in closures of private colleges. Public colleges may have trouble convincing state legislatures to fund them amid declining enrollments.

Grawe argues that colleges might be able to avoid closures and budget shortfalls if they can reduce their dropout rates and focus on keeping students — and their tuition dollars — on campus. Grawe cites the example of the University of Southern Maine, which is coping with fewer students but operating with a larger budget because of its efforts to keep students through to graduation. Expect more colleges to launch “student retention” and “student success” initiatives.

Related: Behind the Latino college degree gap

Of course, Grawe’s predictions may turn out to be wrong. Economists predicted a similar drop in college enrollments in the 1980s following the baby boom generation. Instead, the college-going rate skyrocketed. Women started going to college in larger numbers. More young Americans wanted a college degree as it became more difficult to get a good job with only a high school diploma. Even older Americans went back to school. Colleges had no shortage of students at all.

Could something like that happen again? It’s possible that the Latino college-going rate could surge. It has already increased to more than 70 percent from 60 percent since Grawe first calculated his forecasts using data from 2011 and earlier. But Grawe says it would be a “very risky” strategy for college administrators to cross their fingers and hope this demographic slump goes away.

This story about declining college enrollment was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

The post College students predicted to fall by more than 15% after the year 2025 appeared first on The Hechinger Report.