(Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Imagine you’re a mother whose husband has just left you and your children with $2.00 in your bank account. Or you’re a grandparent raising your incarcerated daughter’s children. Or a father of three with a disabled wife who can’t help pay the bills or raise the children.

With these and other scenarios, a group of Wilmington, Delaware, educators were offered a glimpse of what it’s like to live below the poverty line in a poverty simulation held during a two-day trauma training last summer.

“They let go of their own identities and were given the roles of a person struggling with poverty,” says Deb Stevens, director of instructional advocacy for the Delaware State Education Association (DSEA).

A Lesson in Hard Choices

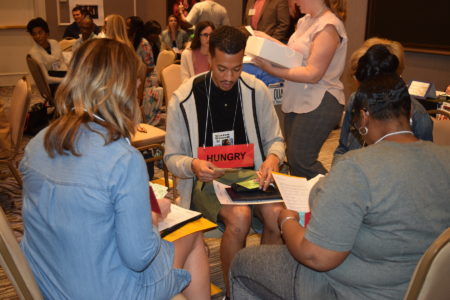

Each educator was given a card explaining their “family’s” unique circumstances and the task of providing food, shelter and other basic necessities with a set amount of monopoly money they were given at the beginning of the session.

Over the course of four 15-minute “weeks” they had to find a way to access twenty different community resources set up around the perimeter of the room. Volunteers staffed resources you’d find in a low-income community with everything from a quick cash and pawn shop to a discount grocery, police station, utility company, daycare center, community health clinic and the department of social services. Some volunteers assisted the family members graciously, others with impatience and rudeness.

Twenty minutes into the simulation nobody had taken the time to visit the health clinic, despite having serious health problems requiring medication.

During the simulation, educators were given a card explaining their “family’s” unique circumstances and the task of providing basic necessities with a set amount of “money” they were given at the beginning of the session.

“Health is the first thing families sacrifice because they can’t afford insurance or hospital bills…” Eunique Lawrence, assistant principal of Warner Elementary told Delaware Online.

Some educators wore “Hungry” signs indicating that they couldn’t afford groceries that week. Some played the role of bored students left behind at school because their parents couldn’t afford the field trip fee.

DSEA president Mike Matthews played the role of a local drug dealer, tempting the educators with fast money or a temporary escape from their troubles. Some “families” were robbed while they were out applying for jobs or buying groceries, other families were evicted, others were denied the federal food assistance they relied on.

The educators scrambled around the room trying to pay for transportation to visit the social services offices, get a job and buy groceries, always with too little money. Most participants ran out of time before they could get the help they needed.

Stevens said teachers were frustrated, but that it imitated real life.

“This simulates what many of the poor go through every day. They encounter long lines and and unsympathetic people,” she says. “It gives teachers a great insight into why a parent may seem frustrated or distracted in a parent-teacher conference, for example.”

Wilmington poverty rate is the highest in the state and 35 percent of children live below the poverty line. The idea for the poverty simulation was part of a larger proposal for trauma education to help educators address student trauma at their schools.

“It helps our educators understand what their students go through at home,” said Shelley Meadowcroft, director of public relations for DSEA. “It’s hard to pay attention when you’re hungry. It’s hard to pay attention when you saw someone shot in front of your house.”

On a more practical level, the participants also said they’d try fundraisers for field trips so that all students could participate whether their parents could afford the fee or not.

Video: Educators in Ohio’s Elyria School District receive poverty simulation training similar to the DSEA training

NEA Grant Helps Fund Compassionate Connections

The simulation was part of a statewide trauma education program created by DSEA and the Delaware Department of Education (DOE) called Compassionate Connections, which a trauma training program kickstarted by a $253,000 NEA grant.

The grant allowed the partnership to create a statewide trauma framework, that allowed all of Delaware’s educators to go through trauma training on a unified continuum.

“We created developmental framework that starts with creating teachers who are first trauma aware, then trauma sensitive, trauma responsive, and and finally, trauma informed,” says Stevens.

What does it mean to be trauma aware, sensitive, responsive and informed? It’s about understanding the root of behavior or absences and finding ways to provide pathways to achievement in class by helping provide access to necessities. A homeless student needs a place to shower. Another student in poverty needs a pair of shoes that fits. Or a hot breakfast and lunch, but also food to bring home through a partnership with the school and a local food pantry or grocery store.

It’s also learning that those who live in poverty don’t expect, or want, handouts.

Equetta Jones, assistant principal of Highlands Elementary, says that while teachers may be extremely empathetic and caring towards students struggling with trauma and poverty, they lack cultural competency.

”Their first instinct is to say ‘Let me help you.’ But you need to hold students accountable, while also meeting their needs. The poverty simulation shed some light on that. They learned that it’s one thing to help students in the short term, but the long term goal is building resilience.”

Use ESSA Funding For Your Poverty Simulation Training

There are three ways ESSA can offer opportunities for social-emotional learning for your school or district.

· Title I: Schools with large populations of low-income students can select interventions that target the social and emotional well-being of these students.

· Title II: These funds support the retention and professional development of teachers. Schools can implement programs that train teachers in delivering SEL, as well as support their own educators’ social-emotional health.

· Title IV: Funds programs that support safe and healthy students and a well-rounded education.

Find out more at myschoolmyvoice.nea.org