Students line up with their books for library in a kindergarten class in Maine. This school’s demographic make-up has changed dramatically in the past decade, over 70 percent of its students are English Language Learners. Staff photo by Brianna Soukup/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images

Sign up today to get a weekly update email from Liz Willen and the stories we published that week.

NEW YORK — This time of year, social media feeds are teeming with back-to-school pictures. Children at bus stops, sidewalks, in classrooms and on campuses. A parade of photos, showing off shiny braces, backpacks and summer growth spurts.

I welcome this upbeat rite of passage, with its iconic images and high hopes for a fresh start. But lately, I’ve found myself casually searching in these photos for evidence of an issue dear to my heart and the work we do at The Hechinger Report: diversity. But more often I see the opposite. For a variety of reasons, racial and ethnic diversity is lacking in far too many schools, both here in New York City and around the country.

And it’s not okay.

There is no U.S education problem more painful and paralyzing than persistent gaps in educational outcomes between black and brown students and their white peers, many decades after the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling that racial segregation of children in public schools is unconstitutional.

And yet, our reporting consistently reveals that racial disparities persist at every level of the system, with racial separation remaining at levels that haven’t been seen since the 1960s.

In part as a result, academic progress for nonwhite students still lags way behind.

That’s why I can’t help noticing, in so many of those back-to-school photos, nothing but white faces. In others, though, I see only nonwhite faces, except for the teacher.

That’s the situation teacher and contributing Hechinger Report author Jennifer Rich found when she departed her leafy liberal arts college in Pennsylvania for an all-minority school in 1990s-era Brooklyn, her first teaching job. “Not one of my students was white,” Rich writes. “Every student lived in poverty.”

Related: Confessions of an all-white teacher in an urban school

The all-white photos I see come from friends and relatives who have chosen largely homogenous religious or private schools for their children, or who live in suburban towns where black and brown students are scarce (like the one I grew up in).

Yet I also have friends who’ve chosen more integrated neighborhoods and schools for their kids. Their photos this week show a mix of children from many different ethnic backgrounds, no easy task to achieve in New York City, where close to half the elementary schools are 90 percent black and Hispanic.

Related: How school segregation hit home for one white father

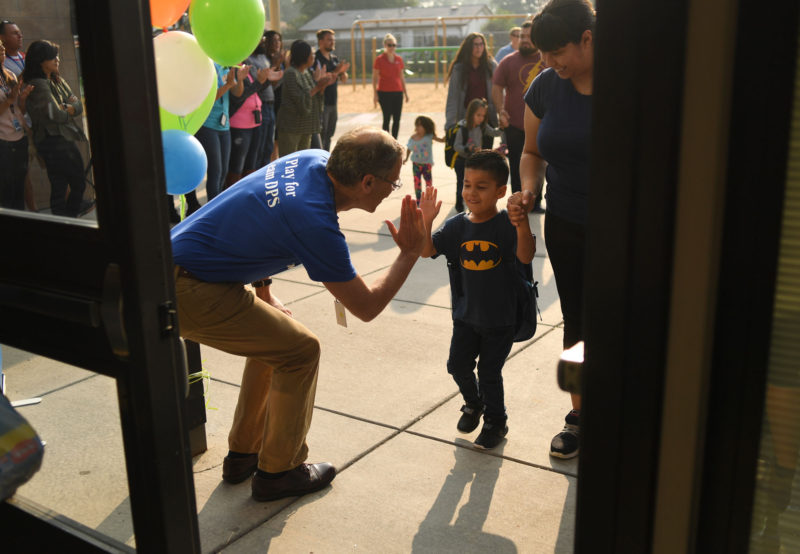

Damian Lopez, 4, gives Denver Public Schools Superintendent Tom Boabserg a high-five as he arrives for the first day of school at Escalante-Biggs Academy on August 20, 2018 in Denver, Colorado. Photo by RJ Sangosti/The Denver Post via Getty Images

Richard Carranza, the city’s new school chancellor, is now forcing a long overdue conversation about changing that racial picture, while acknowledging the difficulty of convincing white parents to believe what the research says: All children benefit from racial integration, something the U.S. government also acknowledges.

Carranza’s path will likely be both fraught and complicated and marked by resistance, as has been the case in other communities we’ve covered that have tried to desegregate.

Related: How the federal government abandoned Brown v. Board of Education decision

Consider the story that Hechinger Report’s Emmanuel Felton wrote last year on white communities setting up charter schools to effectively keep out black children.

We’ve also seen in our reporting that segregation is on the rise even in places still under federal desegregation order. And our work in Mississippi has shown many persistent efforts to keep white and black students separate.

We’ve also reported on the successes of integration in places that have pursued it intentionally, and we’ll continue tracking districts that are bucking the national trends and pushing back against reluctant white parents.

In New York City, we’ll be watching how Carranza confronts this national problem, and listening closely to the voices of students. We’ll continue publishing their opinions and hosting a podcast we help oversee from The Bell.

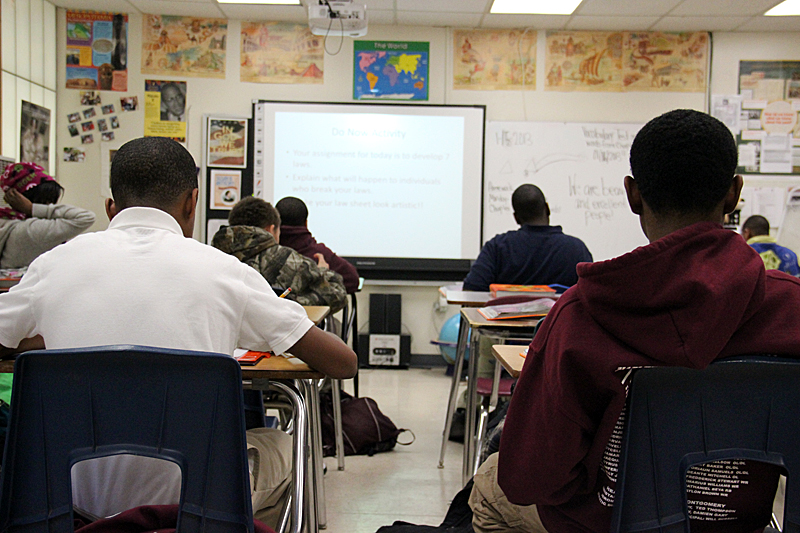

High school students sit in a rural Mississippi school classroom. Only about half of graduates from predominantly nonwhite rural high schools go to college, the same proportion as their counterparts from predominantly nonwhite, low-income urban high schools and fewer than the 69 percent national average. Photo: Jackie Mader/The Hechinger Report

Young people’s views matter greatly here: The city’s students are the ones who directly experience the consequences of inequality, and it sometimes reaches into every aspect of the school day. Some black and Latino students maintain, for example, that they have far fewer athletic opportunities at their segregated schools.

Related: Students sue New York City, saying black and Latino athletes have fewer sports opportunities

I embrace the airing of differing views and a robust conversation from those keeping a close eye on how schools are addressing diversity.

Already, Carranza is igniting ire, cheers and controversy for questioning the need to screen students for admission to the city’s specialized high schools, and for introducing ways to enroll more black and Hispanic students in them.

Change won’t be easy, and if history is any lesson, it will be a long time coming.

I often come back to the day many years ago when visitors and their kids from a white suburban town accompanied me to pick up my sons at their integrated New York City public elementary school.

Why, the visiting children wondered, did my kids attend a school “with so many brown children?”

Progress will come when they instead wonder why there were none at their own school.

This story about school segregation was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

The post Take a closer look at those back-to-school photos: Is something missing? appeared first on The Hechinger Report.